Trust and Betrayal: The Legacy of Siboot

Description official description

Trust and Betrayal: The Legacy of Siboot, also simply known as Siboot, is a unique strategy game by

The game plays on Kira, a moon of the planet Lamina. The Kira colony was founded as political experiment for cooperation between seven divided alien races. After Lamina was destroyed by a nuclear war, the colony was on its own, and a certain Siboot founded a new civilization, based on a universal telepathic language called "Eeyal" and led by a Shepherd. Now the fourth and last Shepherd has died, and there is a fierce competition between the seven acolytes, including you, for his title.

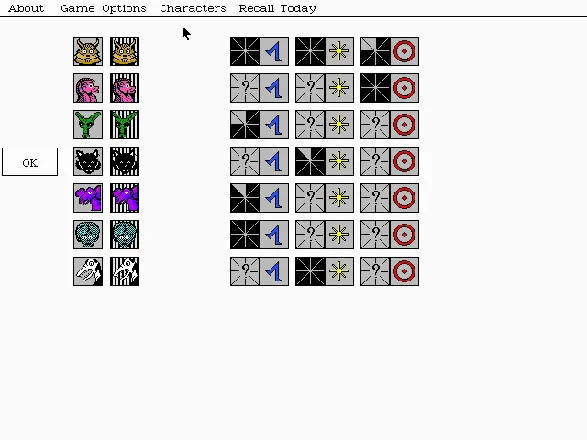

To become Shepherd, you have to collect eight "auras" in three different areas -- tanaga (fear), katsin (trust) and shial (love). At night, the acolytes fight mental duels in a rock-paper-scissors kind, where success depends on knowing the aura ratings of the duelist -- which is why collecting as much information about the others' aura is crucial..

Each morning you awake with the knowledge of one aura rating for each acolyte, and during the day, you try to collect as much information as possible by interacting with your competitors. All this is done an iconic representation of Eeyal, which allows for many ways of interaction like telling, asking, threatening, begging, accusing, promising, yelling, deriding, saying thanks or sorry or just expressing emotion or holding smalltalk. There also is some way of trading information by constructing sentences like "if you tell me the tanaga count of X, I tell you the shial count of Y" -- all this done by clicking small icons.

Each competitor has its own personality, and they fear, trust and love each person differently. Everything you do will have effects on the way the acolytes react you, so you will have to find a careful balance between getting enough information and not abusing your allies. The same holds true for the all acolytes, the NPCs are constantly running around and talking to each other.

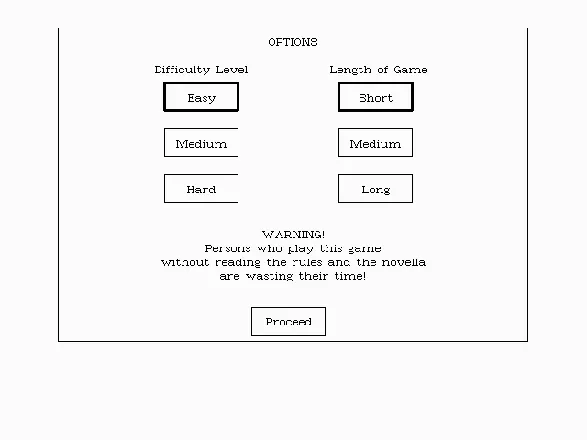

In between all that interaction, the game is interspersed by cutscenes which present you with a certain situation to which you can react in multiple choice style. It offers a save and restore function as well as three difficulty and three game length settings. The game came delivered with a manual and a novella by Chris Crawford which are very helpful to getting started.

Screenshots

Credits (Macintosh version)

11 People

| By | |

| Editor, back-up for riskier decisions, shoulder on which to cry when things seemed hopeless | |

| Consultant on linguistics and psychology, help with design of Eeyal language, artificial personality, many suffestions on overall game design | |

| Most of the artwork | |

| Playtesters | |

| Moral support |

Reviews

Critics

Players

Average score: 4.0 out of 5 (based on 2 ratings with 1 reviews)

The Good

Immersive. A word so often thrown about regarding games like Daggerfall, Half-Life, Wasteland, Final Fantasy, or any classic adventure game. However all these games contain a frustrating and hideous blemish, a common flaw that dashes all suspension of disbelief to ugly little pieces every time it is encountered. What could that be, you ask? The graphics are appropriate and evocative, the story is consistent, and the action is believable enough on the game's terms, the action is free and varied--so what could possibly undermine all that goodness?

NPC interaction! If you've played any amount of RPG, adventure or story-centric titles where the player talks with computer-represented characters, you're familiar with this unique corner of Gamer Hell. We know them by their kinds: the signpost NPC who amiably spits out the same monotonous information at the player who just slaughtered everyone in the town; the exclusively choosy parser game NPC who requires the player to hopelessly guess at what precise phrasing of what exact keyword will yield a desired effect (or indeed any effect); the adventure NPC filled with a soulless branching tree of text that can boast only a few fruits for all the desolate vastness of its foliage--all these interrupt free interaction with the design to force the purposed domination of the creator down the player's throat. And that experience sucks hard, wherever it appears.

Let's put the problem in more understandable terms, bad design for NPC interaction is like bad design in FPS combat. Yet almost all great shooters recognize that providing only one eternal and arbitrary option for success is fun-destroying, and lethal to game variety. Take a game with simple controls, like Doom--on the basic level Doomguy can run, strafe and shoot (with a variety of weapons), either singly or all at once. When confronted with an opponent, success can be reached in many ways, so long as the chosen path is followed skillfully. The player can stand still and snipe from a distance with a powerful weapon, sneak up using cover and shoot undetected, run in wildly spitting ammo from a weaker weapon while strafing, shoot the wall near the baddie with an explosive weapon, etc. Dozens of options are there, and many can succeed if used properly. Now imagine if the -only- way to defeat an enemy was to stand stock still and shoot from an exact distance with only one weapon. With such an exclusive and unchanging path to success, what good is being able to move and shoot? What good is being able to strafe while shoot? What good is sneaking up? What good is having a choice of other weapons?

That's what we see with standard NPC interaction--one defined method of success which requires no skill beyond figuring out the arbitrarily defined method the creator decided was exclusively and eternally correct. Other "options" are only provided as a shameful disguise for the lack of interactivity. There is little limit placed on the ways a player can fight monsters in great action games--the player can decide to employ new techniques and new strategies on a whim, and the game will support them based on a few sensible rules. Yet there is almost always a strict unviersal limit on what roads lead to success when interacting with NPCs. And that sucks for the audience. An audience wants some dialogue with a creator's vision in any art form, not a cruel compulsory guessing game of what the right interpretation is and forever shall be.

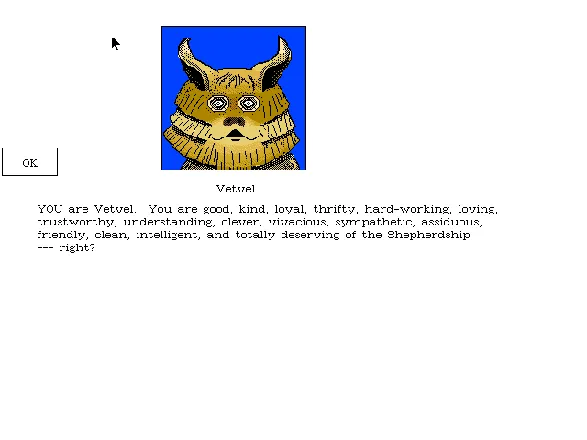

To get back to the actual game I'm reviewing (:-P), that's the endemic problem Siboot decides to conquer. It does with NPC interaction what designers have already mastered with regard to arcade action--it provides multiple paths to success based on a few sensible rules. The player is Velvet, one of several alien races that coexist on one planet and its colonized moon. An individual represents each race as an "acolyte," and these acolytes compete against each other in psychic battles to become the "Shepherd" or psychic leader of all their society. One of three auras can be assumed for attack or defense, and each can defeat one other (think rock paper scissors). Victory in this combat means collecting the defeated aura and adding it to your arsenal--once you collect 8 of each aura, you become the Shepherd and win the game.

The difference here with basic rock paper scissors is resource management--you need to identify who has a vast supply of the auras you need, and then guess the likelihood that it will be used for defense or attack in combat. It is therefore riskier to use an aura that is in short supply, and by this rule of thumb one can guess at the likely choice of one's opponent in a way that is impossible in paper rock scissors. This results in some classic, simple and deep game thinking--will my opponent go with the obvious "best" option? Does my opponent know that I know it is the obvious choice, and therefore reject it?

But that's unquestionably the least interesting game mechanic, as it is very simple. The complexity comes in with the fact that each player wakes up with the knowledge of one aura's count in each competitor's arsenal. To get advantage over a competitor, you need to know the count of every aura he or she has. How do you do this?

NPC interaction! (we got there eventually :-P) The controls have been streamlined for simplicity and ease of use, yet within sensible rules many methods of play will lead to success. Just as that is the definition of great action gameplay, it works here for NPC interaction. Preceding the mental rock paper scissors match of nighttime, the player has the opportunity to meet with the competitors and try to figure out as many aura counts of others as possible by trading knowledge. NPCs that love and trust you are likely to give you scads of information even about their friends, whereas NPCs that hate and mistrust you won't give out information even on competitors they dislike. If they fear you, however, some threats might turn the trick. :-)

Relationships are defined early between the competitors, but they are quite elastic. Revealing knowledge about another's aura count is a betrayal. Betrayals and breaking a promise not to attack or betray will eventually make you hated, feared and mistrusted even among your friends. Remaining loyal and honest while providing lots of information to your friends will make them love and trust you.

Beyond this universal mechanic your emotional tone and expressions of emotion have an effect, because NPCs have personalities: some enjoy frivolous conversation, some have little patience for it; some take well to flattery, some respond to honesty and morality; some are loyal, some feel free to betray their truest friends. You are not the only one who can betray friends or break promises, and you are not the only one who is subject to shifting favors as a result of these activities--all the other competitors can interact in the same ways with each other with the same possible results.

This depth allows the player to take on whatever persona desired, so long as it is done skillfully. Want to be an ethical, honest person? It can be done by holding fast to your friends and punishing your enemies. Want to deceitfully play all sides against each other ruthlessly, with no regard for friendship or trust? Feel free, as long as you go about it intelligently. Want to turn best friends into bitter enemies? Want to be loved and feared by all? Go for it! Even seemingly impossible goals can be met with enough skill. Almost all interpersonal strategies that seem like they should work -will- work, and the demand on the player's skill scales reasonably with the ambition of the strategy.

It's an absolutely marvelous feeling to play out different interpersonal strategies, exploiting the starting relationships and individual personalities with the game mechanics to make the social world of the game into whatever you want it to be. There's no arbitrary technique to reach success--a cruel faithless player can win just as easily as a kind loyal player. The difficulty comes from tailoring your strategies to the personalities and maneuvers of the other characters, not from figuring out the keyword or bauble or precise sequence of soulless menu selections that will yield success in the same way every time once discovered. A strategy that worked with a character once may not again. Your flattery won't yield information anymore if a character comes to mistrust you. If a character no longer fears you, your once productive threats will be scorned and dismissed.

It's remarkable. It gives the freedom of decision and encouragement to explore new ways of play that are taken for granted in action sequences, but for some reason aren't demanded in social sequences. Gamers need to stand up and fight for their right for believable, worthwhile social interaction with NPCs in games. That doesn't require a well-written script or zillions of features and options, it just requires a great mechanic, a few available actions that can combine into unlimited strategies for success, and intuitive rules to govern the behavior as the player would expect.

Siboot does all of this. And the NPC interaction that lies at the very heart of the game is incredible.

The Bad

Being a trailblazing game, one shouldn't expect perfection on all fronts. This game reached its primary destination, but smoothing the road has been left for those who should have followed. Just as we have seen incredible 3d and physics engines built on the shoulders of innovative but necessarily flawed simple predecessors, this game points the way more than it perfectly reaches the destination.

First, the mental combat is all that remains outside of interaction, and it's rather mundane and unexciting. It offers barely more strategy than rock paper scissors, although the way it does so is rather ingenious. This strategy sequence, as well as the bizarre setting and plot for the game, are easily identifiable as an excuse for the social focus and resulting limitations of the game's design.

And there are limitations, but this should come as no surprise. They do seem more obvious perhaps because we don't take the limitations for granted in a new genre. For example, a player in Siboot cannot lie--anything you tell someone must be the truth. This limitation leads to the obvious question: "Why can't I lie as in real life?" The answer? "You speak in an alien telepathic dialect, necessary to unite the varied cultures of your alien world, and, this being telepathic, lies are impossible." How unrealistic!

True, but remember platform games? They are more abstract in their presentation and freedom than the latest 3d FPS, no? In most platformers, the world is two dimensional. "Why can I only move in two dimensions, like in real life?" The answer? "Uh, there are these things called metroids, and you're searching for them in the tunnels of the alien space pirate base where they're kept, and, tunnels being cramped, you can only go through them or up and down them." How unrealistic! Still, with an elegant play mechanic and sensible rules, these games can be enormously fun despite their lack of realism. Realism on its own can impress, but it is not always necessary (or helpful!) in making a game fun.

The ending is unrewarding, the story is rather strange, the strategic combat that will actually -win- the game for you is too simplistic, and the interface (while perfect for the game's limited view and bursting with available strategies) makes you long for more control. However, all these are forgivable in light of it being such an innovative, fun, and brilliant game.

The Bottom Line

Anyone disgusted with the rote signpost/keyword/menu-button NPC interaction in almost all games needs to give this a shot to see what is possible. It turns out to be quite a lot. Give credit to Chris Crawford for trying something immensely original and unique that was doubtless an immeasurable and uncharted mountain of hard work. The design and focus of this game are unlike anything seen before, and proves that NPC interaction can be as lively, varied and strategic as any twitch arcade experience.

Macintosh · by J. P. Gray (115) · 2008

Trivia

Crawford created a DOS version in 1987 which was never officially released. Years after, he sent it to a well-known abandonware site, so that it can readily be found on the web.

Analytics

Related Sites +

-

Erasmatazz home page

Homepage of Chris Crawford's project to introduce human behaviour and interaction into story-driven computer games, which in a way started with Trust and Betrayal. The source code for the game and other works of him can be obtained too. See especially the library for articles about Erasmatron. -

Storytron

Storytron is a company created to commercialize Chris Crawford's interactive storytelling technology.

Identifiers +

Contribute

Are you familiar with this game? Help document and preserve this entry in video game history! If your contribution is approved, you will earn points and be credited as a contributor.

Contributors to this Entry

Game added by General Error.

DOS added by o0pyromancer0o.

Game added November 4, 2006. Last modified March 31, 2025.